Saudi author Mojeb Al-Zahrani discusses the Kingdom’s recent reforms

[ad_1]

PARIS: Mojeb Al-Zahrani has a profound passion for cultural exchange. Born in a small mountain village in southwestern Saudi Arabia, he arrived in Paris in 1980, aged 23, to study for his doctorate. His choice was inspired by his love of French literature (which he had read translated into Arabic) and because he was “looking for change and diversity.”

His thesis, defended at the Sorbonne, focused on the image of the West in contemporary Arab novels. Having completed his studies, Al-Zahrani returned to Riyadh to teach comparative literature, aesthetics and modern criticism. His ambition was to offer “a different approach” informed by his time in France.

In 2016, he was called by the Arab Ambassadors Council in Paris to serve as general director of the Arab World Institute (IMA), under the chairmanship of Jack Lang.

He has since introduced a number of cultural initiatives at the institute, including the creation of a collection of books on French and Arab personalities — “Cent et Un Livres” (One Hundred and One Books) — in partnership with the King Faisal Prize. The collection focuses on connections between the two cultures and on pushing back against stereotypes, or “those simplistic images that prevent thinking,” as Al-Zahrani puts it.

In 2019, Al-Zahrani was reappointed for a second and, he says, “final” term, after which his goal is to return home to his childhood village.

On a beautiful June morning, with the sun reflecting off the River Seine, Al- Zahrani welcomed Arab News to his office to discuss literature, art, and his role at the IMA.

Q: Who is Mojeb Al-Zahrani?

A: I started my life as a peasant, in a small village amongst the great mountains of southwestern Arabia. Then, by chance, I went to university in Riyadh and, again by chance, I came to France, where I currently work. And today I feel like going back to my small village. I am a big fan of trees and I love the earth. I want to end my life in the same way that I started it. In the meantime, I have worked as a teacher for more than a quarter of a century. I have attended hundreds, if not thousands of conferences, I’ve written seven books and have contributed to two large encyclopedias in Saudi Arabia.

Q: What is the biggest challenge you face as head of the IMA?

A: A lack of funding is probably a challenge faced by all major cultural structures worldwide. We are a charitable enterprise that depends on (donations). The French Foreign Ministry is very generous to us, but nevertheless, we do lack funding. That’s why, at times, we appeal to the generous people in Arab countries.

Q: You wrote a book about the image of the West in Arab novels. Why was that important to you?

A: Exploring and discussing our image of others is something to be done with the utmost seriousness and honesty. France is extremely rich, and each region has its own identity, its own image. The France renowned for fashion and literature is not the same as the “France of the delinquents,” or the “racist France.” These are the kinds of (nuances) that we need to understand. They can help us communicate at all levels and in all areas.

Q: How important is French culture to the Arab world?

A: French culture has been important ever since Napoleon Bonaparte’s expedition to Egypt, which came before the establishment of modern Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Syria, and Algeria. This expedition was not a military conquest in the traditional meaning of the word, since it included more than 500 scientists, who were chosen and brought by Napoleon in order to study Egypt, and to propagate a number of modern ideas. Many historians, literary critics and sociologists see this time as the ‘rebirth’ of modern Arab culture. And up to the 1960s, the great Arab intellectuals were French- speaking. So, French culture is present and appreciated throughout the Arab world, not only in the French-speaking countries, but also in the Gulf.

Q: And what about the other way around?

A: I think Arab culture is an important part of (European) culture too. There were hundreds of thousands — then millions — of people who came to (Europe) as a result of colonization; in France they came from Egypt, Palestine, and North Africa. They came with their language, their beliefs, their heritage, their culture, their literature. In the early 1980s, when I was a student in Paris, there were only a few names of Arab-Muslim origin in the French media. Today there are thousands in all areas — from sports to literature, from music to art. Arab culture is an intimate part of what the French cultural scene.

Q: What about Saudi culture specifically?

A: Saudi Arabia is an English-speaking country. So you cannot expect Saudi culture, in the broadest sense of the term, to be present in France the same way as the Moroccan, Algerian, Syrian or Lebanese cultures are. We really came into the Arab cultural scene in the 1950s, thanks to the discovery of oil. Before that, living conditions were not (in Saudi Arabia).

Q: You were a faculty professor in Saudi Arabia until very recently. How would you compare the Saudi youth of today to your time as a student?

A: I am very happy, and sometimes even surprised, by the opening of the doors (of Saudi Arabia). I’ve been one of what you might call the “critical intellectuals” or “modernists” ever since my university years, even before I came to France. We always had the aim of improving the situation of women, to change society a tiny bit, to open up even more to the outside world. Now, when I return to my little village and I see young female students driving their cars, smiling, I tell myself that the goal of our whole cultural life was to achieve something

similar to this.

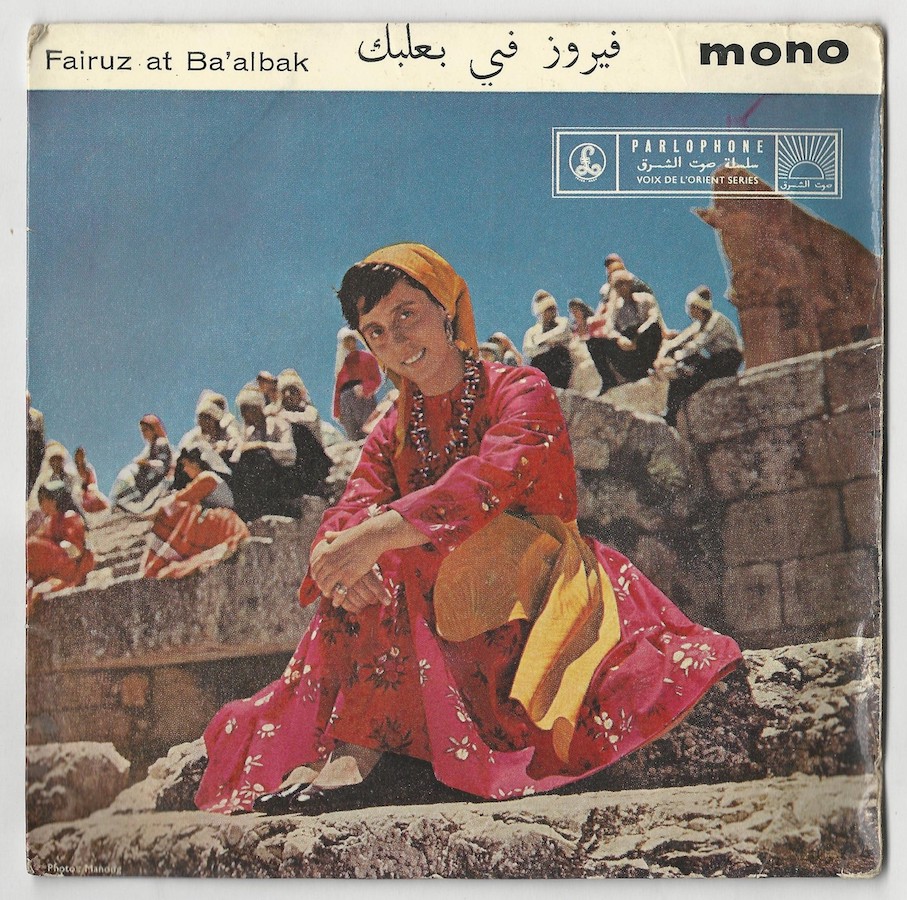

Fortunately, there is now a great spirit of openness and support for cinema, for the arts in general, as there used to be. I am part of a generation that venerated Umm Kulthum, Fayrouz, Sabah, Warda, and many other famous Arab singers — men and women — who we would see on Saudi television when it was still black-and-white.

Q: You are a role model for the younger generation of Arabs, and for young Saudis in particular. What message do you have for them?

A: I’d use the peasant, rural-inspired, metaphor: “You reap what you sow.” I hope that we can diversify culture and arts even further, in a modern world that is evolving very quickly.

Adapted from an article originally published by Arab News France.

[ad_2]

Source link

We use cookies to optimize our website and our service.

We use cookies to optimize our website and our service.

Responses